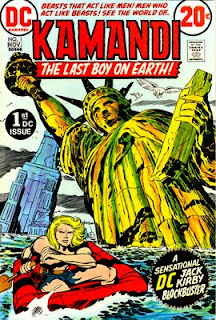

…and Origins (this day, the anniversary of Jack Kirby’s birth.)

Along came The King—Jack "King" Kirby. The man who created gods and immortals and who became that for the child-me. My strongest influence, my greatest teacher, the man who decided the direction of my life at the age of ten.

I wasn’t there for Marvel’s flagship books. I missed Fantastic Four #1. I missed The Incredible Hulk #1. I was out of the proverbial “loop,” regarding what was cool (see: story of my next 40+ years). While I was happily scribbling away, trying to copy Alex Raymond, Hal Foster, Stan Lynde (and a legion of others) from the Sunday funnies, and I was already bored with Hot Stuff and Casper, and I had just discovered comic books on some of my favorite TV shows like Twilight Zone, Thriller, and Outer Limits, and then Classics Illustrated—to a childlike understanding of such things, the art sorta resembled my Hal Foster—and just this year I had discovered great comics like The Flash, and Superman’s Pal Jimmy Olsen, other “cool” kids were already off to the races and collecting that which I was yet unaware.

And I would exhaust my 10c purchase, sometimes scribbling in the margins or tracing whole pictures with a ball point pen (Oh, the humanity!), and trade those comics with other “uninformed” (not-cool) kids because, hey, 10c was a lot of money to a ten-year-old in my neighborhood.

If I came across the occasional Journey into Big Ugly Monster of the Month comic book, it naturally got the same treatment. Titles were interchangeable, I was already focusing on the quality of the picture-making…

…then HE happened. The King.

Kirby was brought into my life one sunny summer afternoon, shortly after I met the new kid in the neighborhood, moved in just the other side of the playground (one of the cool ones, who shall remain nameless—for reasons that will become obvious). He was “into comics” like myself, was trying to draw from them, like myself, and he knew all about comics (not like myself). And to keep the friendship alive, we began trading comics.

Then, even to my struggling ten-year-old intellect (as opposed to my struggling old-man intellect), I began noticing a pattern to his trading practices. He was turning down some of my occasional offerings for trade. Why, you may ask. I wish I had asked that about six months earlier than I did. Then the reasoning came slowly to light as he explained to me one day the logic of why I should trade him two of my reasonably fine 10c’ers for just one of his. He told me his was worth more to him. And then he talked me into trading my reasonably fine (if drawn upon on page twelve, which I’m sure he didn’t see at the time), for a Marvel comic book that was indeed, and obviously, coverless. He said, “Just look through it.” I did—and I made the trade.

I stared at the first, coverless, page for at least fifteen minutes before I left his doorstep for home. I believe I also stopped at the corner streetlight for another fifteen. Then I went into my room and spent the remainder of the day, until mom called for dinner, and then went back after dinner. I believe she thought I was sick. I guess I was. Heartsick, as in love.

I went into a comic buying frenzy, sometimes three to four 10c’ers a month. Always looking for Kirby. I was still trading, because I could not possibly get to see the glut of titles that hit the drug store each month without giving up those I had purchased, but hey, I’d already exhausted those, hadn't I. Time for new ones. Even when devastated by the incredible price increase to 12c. Then Annuals and "King Sized Specials..." Awww—c'mon!

And my “new best friend,” the cool kid who turned me on to Thor, Spiderman, The Hulk (who is still remaining nameless), was diligently watching me, trading me, strategically, getting those books for himself that he needed…

…until that fateful day, about a year later, when I (in all my newfound comic coolness and wisdom) discovered his method-without-madness. He invited me into his basement to see his “collection.”

There, on the floor, along the basement outer walls, was stacked the greatest accumulation of comic books I had ever beheld. All Marvels. All separated into tidy stacks according to title. I felt the growing lump in my throat (no, not a tumor), the lump of regret. Why had I not been in on this? How did I not understand—this is what comics was for?

He held some up for me to behold. “No, don’t open them, I want to keep them in good condition.” Some of them were books I had traded to him almost a year before. And those books were still cool. And they were tidy. And I WANTED THEM BACK.

Of course I never said that to him. Even then I understood the protocol of finders-keepers, and you gave it up, it’s mine now.

I went home. Revelation. End of the world kind of revelation: I was ten years old, and I was the stupid kid. I had been betrayed. Sure every kid experiences the betrayal by a friend many times before he learns to become a jaded adult, but this was different. I didn’t just collect comics. I loved them. I studied them, every line, every inch, every panel, not just for the superheroes pummeling themselves month after month, but for the art. I should have saved the art. I sunk into one of my deepest depressions. I was almost twelve.

Slowly I came back. I bought a few more comics, what I could afford, still looking for Kirby.

And month after month, I laid on my bedroom floor, still tracing the drawings of Thor, The Hulk, the FF, then he gave me Captain America (the greatest hero the world had ever seen), Sgt. Fury and the Howling Commandos, and then even more, The Avengers! OMG! (even though it would be forty years before I knew what OMG meant) and I was drawing (copying) on my own, not well, but focusing, struggling to get better, to be like Jack Kirby.

I don’t understand. It looks easy. Nothing complicated. The muscles are round. The speed lines showed Thor falling. The buildings are blocks in perspective (I learned about perspective from Jon Gnagy, after all). But I don’t understand—why can’t I make it look like Jack Kirby? Try again. Fail. Try again. Sometimes the same picture over and over. Always a fail. Try the next panel. Try the next.

Some might say obsession. Okay, I’ll be the first. Obsession. (There, happy?)

But it was all because of Kirby.

Sure I found others—who could not fall in love with Spiderman (Ditko) (whether I understood the attraction to the quirk(ier) line-work or not) or Iron Man or Daredevil or Sub-Mariner (Don Heck, John Romita, Gene Colan)—and each new Marvel artist was a revelation (the good kind), and each stylistically unique, but each and every artist was wonderful to this struggling wanna-be. And the artists, one after the other, started flying off the stands at me like…like Jack Kirby superheroes. I needed more. I wanted to understand the how and why of the lines. No matter the style. How did this one work, even though different from the others?

I was unknowingly developing the Genesis (word one, page one) of my own style by the mere exposure to so many disparate, great styles. I was no longer just trying to draw like Jack Kirby, but some immature, unhappy amalgam of all of the above and more. Learning by inches. Then I discovered John Buscema, and I reached for the next rung in the developmental ladder, but whenever I began to feel the slightest bit insecure about my own drawing, got frustrated with my inabilities to capture correctly what my mind was seeing…

…I always went back to Kirby. Like the old headmaster of legend, waiting for me to fall down so he could step in quietly and whisper, Remember your origins. Remember why you fell in love. It’s all right here in my lines, my figures, my simple (yet not simple) compositions. Open up the old comics. Understand the fun you had. The power I gave you. The essential, enigmatic something in the way he threw his lines onto a page, that brought his heroes and villains…off that page.

Afterward:

I had been working as a comic book artist for quite a few years, I had just recently moved to the north Valley of L.A. because I wanted to move on and into the film business, when I read of Jack’s passing. The news struck me like Thor’s hammer. My greatest hero was gone from the earth. I had never met the man. Never spoken on the phone. Never got to tell him of his influence in my life. How he was responsible for so much of the “good stuff” that was a part of me. (And that maybe I would be better if I had only followed his cues a bit more closely.) But he was gone. The opportunity was gone. I didn’t know his family, but I stood at the back of the modest hall at his funeral, listened to others who knew him better, could put into words the many things I knew about him, and more, about the man, his legacy. I didn’t cry, but my heart ached at the loss of him. I went home and surrounded myself with his comics, poured over them once more, this time not to learn anything new, but simply to remember. My childhood washed over me.

Jack Kirby, while my work eventually deviated greatly from his influential hand, he was my greatest teacher. The single most powerful voice in who I became, professionally speaking. Had I ever met the man, any words would have been insufficient—save these: Thank you.

Love you, Jack.

J