This thought-stream began as a question posed on

social media, I got involved until, as social media so often goes, the white

noise spilled over. But the topic remains important (hence my desire to continue

it here as a soliloquy). Decisions made by the wrong people, those in positions to influence and affect

change, can force a deterioration of art in all its forms and we are all the

poorer for it. It’s called strangling

creativity with the power of authority.

(I include my previous comments throughout as a

means of contextualizing. I leave out the opposing voices because…well, frankly, I don’t

respect them enough for inclusion as they are in fact deleterious to the

definition of true art. If anyone is interested in an expansion of these opinions

on art, I refer you to my earlier posts: "The Transference of Emotion" and "Art is Objective."

Here is the initial question:

“Because many

contemporary representational painters emulate the art of the nineteenth

century we repeatedly see nostalgic paintings of models in period costume. Is

such nostalgia healthy for contemporary representational art? If it is, why? If

it isn't, why not?”

*

The world is far too large and diverse for many

people. Some feel the need to define what is in the world’s best interest,

regardless of those who may disagree. Sad to say, many in the art world operate

under those same misconceptions.

First, let me acknowledge that I have my own set

of standards—naturally—likes and dislikes in the world of art and were it up to

me, feces on a canvas would go nowhere other than a landfill far away from me.

However I would never tell an artist (or a monkey) he is un-healthy for contemporary…well, perhaps

in this case…and he should never shake my hand.

Moving forward, let’s examine the operative word

to follow, “relevance.”

Pertinence.

Practical and especially social applicability. “Artists and writers strive

for relevance in their own time.” But

should they and who decides? The words social applicability indicates that it might be the society that ultimately determines relevancy. And,

whether pertinent to culture or society or art itself, can so large a segment

achieve consensus on a single artist’s relevance before many years have passed?

Legacies are never felt before an artist’s

passing.

This is an important issue to me, as it should

be to artists everywhere, after growing up during the puritanical-like reign of

the gallery power brokers of sixty years ago. I call them The Art’s Dark Ages,

because it lasted nearly as long and destroyed many artists with their

lord-like overreach.

Much like the Pope chose to tell the population what art was acceptable in Michelangelo's time, the decision makers in NYC who, in order to become relevant themselves and define their own self-worth in the art world, chose to tell the world that a large amount of art being created was “irrelevant.” And they were to tell us which art was important enough for the rest of us. (Naturally, this drove up the prices of inferior work in their galleries making many who would otherwise have remained anonymous, noteworthy.)

Much like the Pope chose to tell the population what art was acceptable in Michelangelo's time, the decision makers in NYC who, in order to become relevant themselves and define their own self-worth in the art world, chose to tell the world that a large amount of art being created was “irrelevant.” And they were to tell us which art was important enough for the rest of us. (Naturally, this drove up the prices of inferior work in their galleries making many who would otherwise have remained anonymous, noteworthy.)

Anything that came before, all of the struggles

of artists and art schools everywhere, all of the teachings of the great

masters, the work of tens of thousands perfecting their crafts to the best of

their abilities, as well as the contemporary greats who rose to the top due to

hard work and intuition and sparks of genius, they would all be denounced as dated, or kitsch, or lacking innovation

and foresight. Unique was prized over ability, the outrageous replaced talent

and knowledge.

Norman Rockwell spent much of his young life

idolizing other great painters. He struggled to be as great as J.C.

Leyendecker. Then as he became the most celebrated artist in the country, his

name a household word, copies of his art in tens of thousands of homes across

the US, along came the elite of the art world, most of whom would not know

which end of the brush actually touched canvas, the decision makers, the king

makers who declared to the press that representational art is passé. Norman Rockwell is a fine “illustrator,” but

illustration is not “Art.” Not with a capital “A.”

Who was the

first to decide this? Who would draw the original parameters of what

constituted Art? Who was appointed to decide this for the rest of us?

And all the other illustrators fell into line

behind him, shunned by the New York intelligentsia. Those who

knew better than the rest of the country and were on a mission to keep us

informed for our own good, for the good of Art. And they did for half a

century.

And Norman Rockwell struggled to be recognized by the Fine Art

world.

And here we find ourselves, all these decades

later, and representational art has risen Phoenix-like from the ash-heap of

contempt, Rockwell’s reputation, by the sheer virtuosity of his performance

garnering top dollar at auctions around the globe. His name is once again

spoken of with reverence by those who understand the work. Others through

diligence to the form, hard and often heart-breaking work, have regained a

modicum of stature amid the multitude of struggling wannabes as art schools and

universities and colleges open their doors and pour forth streaming legions

of new artists on an annual basis, all struggling to make their own individual

marks. All wanting to be noticed. To be respected by their peers. To be important.

Today we find ourselves faced with voices within

our own ranks, artists critiquing other artists with the sole purpose to drag

the spotlight in their own direction. They have become the new arbiters. They

have chosen themselves as deciders,

we’ll refer to them as the “arbiters of

relevance,” letting us all know what is or is not “Important Art.”

Perhaps it is the need to shrink their world

down to manageable size. Control issues.

Perhaps if they limit those around them, their own work will appear more

important. They will become more relevant.

In a world of working for the love

of art and competing with oneself in a never-ending effort to be better than we

are, we now have many who have decided that the only way for them to appear to

grow is to restrain others. Tell the world they are more important than the

rest.

The death knell to evolution is complacency.

The natives have begun eating their own. What they

fail to understand is the harder they try to look relevant, the more desperate

they appear. The box they have drawn themselves into (pun intended) has opaque

walls and they have lost the ability to see value in anything that does not

resemble their own.

As to the initial question, a few of my aforementioned

responses:

Criticizing an artist's work based on genre or

subject matter alone is the true disservice to the art world. All art, whether

it's dance or writing or painting, is about communication and emotion, as well

as the expertise of the artist. The greater the emotional response for the

viewer, the more successful the artist's intent is realized. There is room in

the world for more than one approach and the narrowing of definitions is merely

the fault of the critic.

*

Too many "artists" trying too hard to

be relevant, rather than working to

perfect their craft. Like a writer working at being "topical," or

hammering the reader over the head with what they deem a popular theme or

political opinion, artists working hard at being relevant, with the exception

of very few, disappear from history as soon as their POV goes out of fashion.

Compete with no one but yourself. Paint what you love and, if you're good

enough, your audience will find you.

*

In 1885 Ilya Repin painted a scene from 1581. (Ivan the Terrible murdering his son.) To

him, his history was important. Hardly kitsch or sentimentalized. Certainly

emotional.

Alphonse Mucha painted history. Waterhouse painted mythology. N.C.

Wyeth. Howard Pyle. Dean Cornwell. Frank Schoonover. Harvey Dunn. In 1400s da

Vinci painted Christ. In 2014 Howard Terpning, whose fine art reputation rests

on his skill at representing North American plains Indians—it could be said

that he changed 20th C perceptions of the tribes and helped make the western art

genre popular to gallery patrons—sold for a record 1.9 million. I rest my case.

*

"Representational art is dead." This

is the same limited thinking that insisted sixty years ago that Rockwell was

"not relevant," merely an illustrator and not as worthy as a flat

depiction of a Campbell soup can or Lichtenstein stealing the work of other

artists and enlarging their comic book panels onto canvas, pissing in a jar

with a crucifix and throwing dung onto a canvas…

My point is that relevance is in the eye of the beholder,

those who refuse to read the futurists or the historians have merely limited

their own knowledge…

And I make no excuses for my work. Those who

seek so desperately to limit the confines of creativity and draw stark borders

around art's definitions, need to expand their own horizons a bit.

If another artist doesn’t share my love, it

doesn’t make him wrong; it doesn’t make me right. My relevancy as an artist

will not be determined by him. If I am good enough—and lucky enough—my audience

will find my work. The larger the audience, the greater the legacy, and if my

work disappears with time, then I have painted for myself and I’m quite okay with that.

I grew up with the gallery, boy’s

club, ignorance of the 70s, so it's an important issue to those who felt

creatively stifled by this sort of narrow vision. I had one prominent gallery

owner tell me I should paint in pastel colors because wives usually chose

paintings to go with their decor. I was told what subjects were popular. Follow

the largest audience.

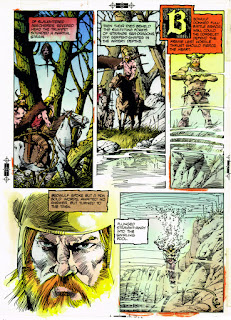

I made my early living drawing comic

books. I was told whose style I should mimic, it was a job.

My first graphic novel was drawn

without the standard word balloons. It was the translation of a poem and I

wanted it to be read as such. I was asked to sit in on a panel discussion with

a couple other artists and the question was posed: “Are word balloons an archaic

artifice now that you’ve made these popular books using only captions, and

should word balloons be done away with? I remained mostly silent because I

could not understand limiting the art form with a new set of parameters. I had

used it to my own particular ends for this particular piece of work. I didn’t

understand throwing away volumes of content for what might be a passing style.

Then when I was first invited to a signing

at a French university, I had no idea that comic book art was considered

"Art" and displayed in actual art galleries all across Europe.

American galleries thought of it as trash.

Over many years I’ve painted just

about anything imaginable: science fiction and fantasy, wildlife and still life

and studio models. When I matured, I decided to paint what I wanted and hell

with what others said they wanted to see.

I studied for a time with a world

class portrait artist. He found joy in the colors, values and landscape of the

faces he painted. He asked if I had those same desires. I did not. I came from

an illustration background and I wanted to tell stories with my art. To paint

the history I spent fifty-some years studying, the personal, the drama, the

pain and the beauty, and occasionally, the ugly, and I realized how little the

average person knows about history. I felt I had a job to do.

Do not define yourself by what others think you should paint, but ONLY what

you choose to paint.

I don’t tell others what should drive

them. I don't pat myself on the back in public, and I don’t criticize other artists’ work (unless they prove to be unworthy

of their own ego.) C=EMS ² (Criticism=Ego x Mouth-Size ²)

—And I tell my students to do the

same, find their own niche, enjoy the work and the learning, because true Art

is very personal. Tell your story your way, even if it’s just a story of paint.

An artist’s life is about learning and giving of what he/she has learned. "Legacy" (relevance) is what is passed down to the next generation and the next. If

the heart is not there, there is no Art.

And creativity is, and should always be, un-limiting and

unlimited.

—Jerry

*With apologies to Ilya Repin for using his paintings of historic import to make a 21st Century point.

*With apologies to Ilya Repin for using his paintings of historic import to make a 21st Century point.