Teachers: Norman Rockwell, Al Parker, Jon Whitcomb, Ben Stahl, Stevan Dohanos, Robert Fawcett, Harold von Schmidt, Peter Helck, Austin Briggs, John Atherton, Fred Ludekens, Albert Dorne…

The Famous Artists Course.

The Famous Artists Course.

“You can be a successful Artist!” —with a large exclamation point, screamed out from the inside back cover, sometimes the back cover, of my comic books month after month. So for a kid who had already spent a good number of years isolated in his room while his friends were outside wasting time on such mundane pursuits as catch baseball, riding bikes, sledding or ice skating in the winter (my fingers nearly fell off at forty degrees, forget that!), lying on the floor gouging pencil into paper, trying desperately to copy those incredible, action-packed interior pages rendered by the mysterious and elusive Golden Ink-Pen of the Gods, as a boy of twelve with the beginnings of what would be my own personal Devil’s Tower built entirely out of sketchbooks and any loose scrap of paper I thought to draw on and save, I was ready, damn-it! I knew how to draw, damn-it! And yes, I knew how to swear at twelve…damn-it!

So I found mom’s scissors and carefully disfigured one of my treasured twelve cent comic books to get that intriguing coupon promising FREE something-or-other from the “Institute of Commercial Art, Inc.”

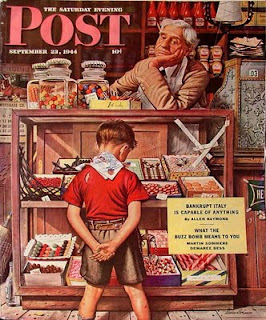

I filled in my name, thought for a moment before crossing out the “Mrs., Miss” in front of the name line. I begged mom for an envelope and stamp. And after a lengthy discussion and much enthusiasm in showing her the advertisement with the now missing coupon, listening to her well-played argument about five-cent stamps not being free, but knowing she would eventually give-in because that was Norman Rockwell in the picture selling this FREE thing and she loved Norman Rockwell—she had shown me the magazines when they came in with his unbelievable paintings on the covers and I could tell by the joy on her face she admired this man.

She was also almost solely responsible for my art addiction from an early age (I’ve already told the gripping tale about her drawing happy faces for me as a two-year-old). At five I would kneel on the chair at the dining room table while she painted masterpieces of Alice in Wonderland and South American parrots just by staying in the lines and following some bizarre numbering system for her paints. For my tenth birthday she bought me Jon Gnagy’s Learn to Draw Set and I copied boxes in perspective, telephone poles and railroad tracks in perspective, and apples not in perspective without knowing what perspective meant, and I dirtied my hands, elbows, and everything within reach, in my first experiences with the raw charcoal stick. Now she just HAD TO LET ME GET THIS FREE, I repeat, FREE PROMISE FROM NORMAN ROCKWELL!

I had found my calling and all it needed was a stamp to shift into overdrive…well, at that age the analogy might have been akin to pedaling downhill to my destiny.

The mailman took the envelope—I know, I watched him—then I waited. Then I forgot about it until I could save another twelve cents for a trip to the drug store to chose my one comic. There was that glaring Norman Rockwell month after month with his paintbrush in hand and an expectant look that said, “So you gonna draw, or what?”

Sometimes it was Albert Dorne selling pretty much the same thing with the same promise, but I didn’t know who he was and his eyebrows sort of intimidated me at the time.

Eventually that day came. I had long given up hope of ever fulfilling my destiny due to a coupon wasting away in the dead letter office behind some postman’s wayward bag, with my mom’s five-cent stamp and her generosity wasted. I went on with my life as before diligently scribbling away, frustrated at not getting those Jack “King” Kirby characters to look the way the King drew them, but persevering nonetheless—I had inherited my father’s stubborn Irishness if little else.

I remember lying, my head and arms dangling over the side of my bed so I could draw on the floor, my head filled with blood and gravity and my fingers and arms about numb from the same, when mom came in and dropped the envelope on my bed. She smiled.

I immediately forgot whatever great new comic book character I was in the process of creating, tore open the envelope to find that my FREE destiny was a thin catalogue describing…

…the not-so-free, several hundred dollars paid in monthly installments plus the opportunity to buy their preferred oil painting supplies, correspondence course.

I didn’t bother to ask mom. Her smile tilted as she reminded me for about the thousandth time, “See, dear? Nothing’s free in this world,” and “You’re a wonderful artist anyway.” That's mom.

I would never ask her. Several hundred dollars to a working class family in 1965 would’ve been like me asking my parents to buy me a car at the age of twelve—that would be quite a few years later and I paid them back, because that’s how we did things back then.

Five years later I would ask to go to the American Academy of Art, downtown Chicago. I spent the summer after high school graduation working on a Budweiser truck, lugging cases of beer in and out of taverns and grocery store refrigerators, building my back muscles, in order to go to that school for a year. (I wasn't "of age" and not legally able to work the truck, but dad knew a guy....) The following summer I joined the military. I missed being sent to Vietnam by about three months.

It was many years later, I had finally gotten freed from the Air Force, I got my foothold into the world of drawing comic books for Marvel and DC, I had improved by leaps and bounds and was starved for knowledge. I wanted—no, I needed to be better. Not because someone told me I should be, but because that drive had been burned into my R-Complex—that reptilian brain of the basal ganglia hanging for dear life to the top of the spine. The drive had been burned there by over twenty years of struggle—and possibly reverse evolution—to improve, and now it would never relinquish me. I had too much to learn. I could see the problems with my drawing and painting and was growing but not fast enough. Never fast enough.

Then it happened. Lightning.

I was in the habit of buying anything I could find with art from the world of illustration. Bookstores became my habit. Used bookstores contained hidden treasures. The sale circulars with garage sales. I only looked for books.

One such sale was in a literal garage. A small warehouse of a garage, gray and dark and I picked through every box of the two-hundred-some-odd boxes and I found my treasure.

Three incredibly large, incredibly heavy bound notebooks, and on the cover the words, “Famous Artist’s.” I wanted to hug them.

I searched the darkened warehouse for the landlady, hoping she had not seen the look on my face when I found them, hoping I might be able to talk her down from whatever astronomical price she would demand for relinquishing them forever. I steeled my nerve and prepared for the worst. I formulated my debate, predicated on the decades of dust, dingy with scratches on the covers, the interiors were not pristine, she would have to take that into account. There was supposed to be a fourth notebook that was missing. I needed the full collection. I was prepared to walk away if the price was too high…no, I wasn’t.

I found the landlady standing in the doorway with her coffee and cigarette, talking on the phone to someone of absolutely no interest to me. I stood until she noticed me with my arms full of Famous Artists Course. She pulled the phone away from her ear. “Found something then?” she asked as if she didn’t know, couldn’t see the greed in my eyes, the desperation, smell my fear with all her feral instincts of the ocelot I knew her to be. A smoking, coffee-drinking ocelot.

“So,” I hid my nerves behind a professional actor’s mask, “What do you think you’d want for these here?”

“What’s that? Oh, those, I really loved those when I was younger.” I knew it! Here it comes! She knows I’m weak…. “How about forty bucks?”

“Sold!” I wonder to this day if she ever got my tire marks off the curb in front of her garage.

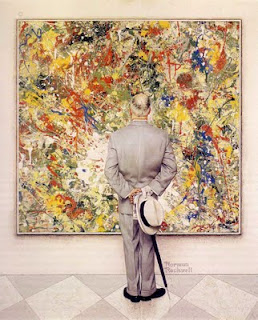

I still consider it the greatest buy of my life. All those names I mentioned in the opening, the greatest of the illustrators using examples from preliminary sketches and detailed drawings, giving me a peek into their “process.” Those books did what no other book in my large collection ever did. They taught me how to think like an artist. Hundreds of pages of not just how they painted, but the decisions they made before painting, why they made them and made the alterations to otherwise fine drawings and illustrations. Thousands of decisions and answers. Not merely a peek under the magician’s cloak, a month spent living in his closet studying his playbook, and him taking my hands to help move the magic through my fingers.

It was lightning and I’m still smoldering from the aftermath. I need to revisit those books every few years, reread, try to remember all because there is just so much stinkin’ information between those spines. But I am glad every time I do. And I'm still grateful for those original masters, Albert Dorne and Norman Rockwell who decided over a telephone conversation back in 1948 to take the time out of their busy schedules to create a teaching resource of this magnitude.

If you ever find this dusty lightning for yourself, grab it.

J.